Chapter IV.

IN U. S. NAVAL SERVICE.

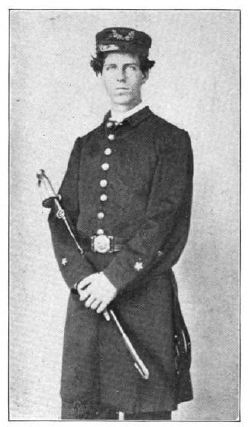

In 1863, I decided to go into the navy, and on a Mississippi River gunboat, as I saw at St. Louis a number of these craft, and the information I had from two brothers who were already in the army, in the infantry branch of the service, seemed to make it clear to me that if I could secure some sort of a commission in the navy, it would be more desirable than going into the army. The feeling in my mind that I must get into the service in some capacity had grown to be so strong that I was now thoroughly discontented with civil life and quite anxious to do my part in putting down the rebellion.

From Congressman Henry T. Blow and one or two business men who were acquainted with Admiral D. D. Porter, I secured letters to the admiral, then in command of the Mississippi Squadron, with headquarters at Cairo, Ill. With these letters I went to Cairo, where I ascertained that Admiral Porter was absent at the time, so I presented my letters to Captain A. M. Pennock, fleet captain of the Mississippi Squadron, who was next in authority to the admiral. After reading my letters, Captain Pennock asked me if I was ready to go into the service. I replied that I was not ready to go in at once, but would be in two weeks. He then told me to report to him as soon as I was ready. I returned to St. Louis and told my friends that I was going into the navy. In about two weeks I again went to Cairo, and after a physical examination, was asked what position I desired, and being “as green as a gooseberry” in nautical matters, I replied “the lowest commissioned officer.” Captain Pennock told

21

his clerk to make out an appointment for me as “master’s mate,” which was done. With it was given me an order to report to the commanding officer of the receiving ship “Clara Dolsen,” a large boat then lying anchored in the Ohio river opposite Cairo, a temporary abiding place for unattached officers and men of the navy.

I found boats plying between the shore and the “Clara Dolsen,” which seemed to belong to the “Clara,” and getting into one of them, having meantime purchased a temporary uniform, I was very much embarrassed by being asked by the coxswain to “take the tiller,” as I had no idea how to steer the boat. My embarrassment, however, was relieved when a man wearing an officer’s uniform got into the boat, as I saw he wore insignia denoting him to be a pilot. I quickly and gladly left the seat I had in the stern and asked the pilot to take it, which he did and also took the tiller. By watching his motions and hearing his orders “give way” on leaving shore, and “way enough” on coming alongside the “Dolsen,”-I was relieved of my fear of displaying my absolute ignorance in the matter of boat steering, which I was afraid to display to the boat’s crew.

I found a good many officers and men on the “Dolsen,” waiting orders to go on board gunboats of various kinds, which were constantly arriving and departing from Cairo. One young man who took the “cutter” from shore to the “Dolsen,” while I was waiting to get on board of her, was a master’s mate, whose arrival on board preceded mine but a few minutes. I found that the commanding officer of the “Dolsen” reported to the fleet captain daily the officers he had on board, in the order of their arrival. The fleet captain sent orders to officers awaiting orders, apparently in the same way, so when a request was received by the fleet captain from the new and large gunboat the “Ouachita,” for a “master’s mate,” this young man received orders to report on board the “Ouachita.” This boat,

22

within two weeks afterwards, ran into a Rebel battery on a river in Arkansas, and in the engagement this young officer had one of his legs shot off, which news, when I heard it, made me rather glad that my ignorance of the simple art of boat steering held me back, as it did, as otherwise in regular order I should have been sent out on the “Ouachita” and likely met with the fate my predecessor did.

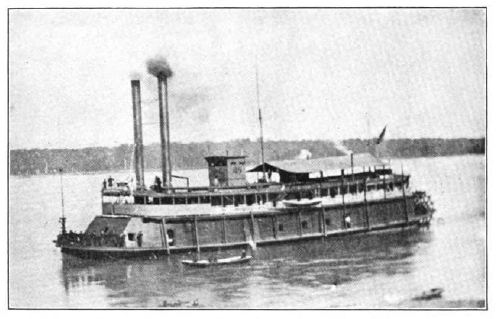

Everything was new and strange to me, so I tried to get information from all navy men I came in contact with. Cairo was a hot and uncomfortable place. I purchased a sword and other outfit necessary and in a few days received orders to report to the commanding officer of the U. S. S. “Silver Cloud.” This seemed like action, to me and I hurried aboard the “Silver Cloud,” which I found, on my arrival, was the style of boat known as a “tin-clad,” armed with six twenty-four pound howitzers, two on each side and two in the bow, also a ten pound rifled gun on the hurricane roof, the latter firing percussion shells.

The boat was about 160 feet long, 36 or 38 feet beam, with 5-foot hold; had a crew of about one hundred men ; was commanded by an “acting volunteer lieutenant” ; was officered by three ensigns, one of whom was executive officer, three master’s mates, besides the staff officers, such as surgeon, paymaster, two pilots and three engineers. There were two officers’ mess rooms, besides the captain’s cabin, occupying the cabin deck, which had two bulkheads across what had been the passenger cabin, the “wardroom,” and the “steerage” with staterooms. The crew occupied the gun deck or lower main deck ; they slept in hammocks and ate their meals on the deck, which was kept clean and white, using clean canvas mess cloths.

The staterooms in the steerage, like those in the wardroom, each had two berths. I was the sole occupant of one of these rooms. Shortly after I had reported to the captain, he sent for me and told me that Captain Pennock wanted him

23

to say to me that if I preferred the position of secretary or clerk at the office of the fleet captain, I could have it. This did not impress me at all. It involved remaining at Cairo, shut up in an office, and would prevent me from seeing the Mississippi river and the towns and cities on it, which I had long been familiar with by name, and would not allow me to lead the active life which I looked forward to as a naval officer. The captain said he would like to have me stay on the “Silver Cloud,” but at the same time, did not want to influence me against what I might consider my best interests. I told him I would remain on the “Silver Cloud” and’ he so notified the fleet captain. I suppose the fleet captain wanted a good penman, and at that time I was a good penman. I was told afterwards by my brother officers in the “Silver Cloud” that they thought I made a mistake in refusing Captain Pennock’s offer, as he undoubtedly would have allowed me to go into active service after a time, if I gave him satisfaction in performing my duties as clerk, and also, which was of more importance than I then realized, have promoted me to a higher position than master’s mate.

I had two friends in the navy, both master’s mates in the Mississippi squadron. I had known one of them in Cincinnati quite intimately and was anxious to see him. They were both on a gunboat named the “Exchange,” which, like the “Silver Cloud,” was an Ohio river steamboat, remodeled above her main deck into a “tin-clad.” I learned that the “Exchange” was up the Tennessee river about one day’s run from Cairo ; also that the “Silver Cloud” would go up the Tennessee. This was pleasant news to me and I had the pleasure in a few days of seeing my friends of the “Exchange.”

The town of Paducah, Ky., on the Ohio river, nearly at the mouth of the Tennessee, which we passed, was the scene of what might have been a serious calamity, but what was, according to my information, a very ridiculous and amusing

24

incident. The men on the gunboats were drilled as “guns’ crews,” every morning, and the routine motions of loading, handling and firing the big guns were all gone through with. A buckskin button was placed in the vent of the gun where the percussion fuse or primer would be in actual firing, and the hammer of the gun was brought smartly down on this buckskin at the command “Fire” during this practice.

While this drilling was going on, on board one of the gunboats one morning, while it was anchored opposite Paducah, to the horror and consternation of those on board, at the command “Fire,” the gun was actually fired, a percussion primer having been placed in the vent instead of the buckskin button. A sixty-four pound solid shot was by this means sent into and through the barroom of a hotel on the river front, and passed between a number of men who were standing at the bar, through a large mirror back of the bar, and then through several basement walls, doing no damage further than the breaking and tearing of the mirror and walls. The people of Paducah heard the gun and were terror stricken, and came rushing down to the levee, to see what was the matter, waving white flags and handkerchiefs.

The captain of the gunboat rushed down to the gun deck in a rage, and inquired “who fired that gun ?” Every one denied being the guilty person, but suspicion rested on one of the gun’s crew, who had served the gun, and he was placed in irons and in confinement in the “brig,” where after a few hours he confessed that before shipping as a sailor man for “Uncle Sam,” he had been a soap peddler and had been arrested for selling soap without a license on the streets of Paducah. So, when the opportunity offered itself, he tried to “get even” with the d d town by putting a primer in the gun and sending the shot into the town, which he said “was a rebel hole anyway.”

25

Apologies and explanations were made to the people of Paducah by the captain of the offending gunboat and the man to blame was severely punished.

My life on the gunboat had now fairly begun. I soon saw that I had made a mistake in choosing the position of “lowest commissioned officer,” to-wit, master’s mate. The next highest position, that of “ensign,” had precisely the same duties watch officer, drill master and log keeper. An ensign’s pay was about 50 per cent more and the ensign messed in the wardroom, which mess consisted on our boat of the three ensigns, the surgeon, paymaster, two pilots and the chief engineer. The “steerage” mess consisted of three master’s mates, second and third engineer and paymaster’s clerk.

I was told that it was quite difficult at first, to keep up a separation of the different ranks on the newly manned gunboats. The pilots especially would not brook commands from young and green “line” officers. On one occasion I had to make formal complaint of abusive language from a pilot who used very profane language to me because I simply communicated to him an order which I, as officer of the deck, had been given by the executive officer to “pass along” at the right time. After a time this difficulty was overcome. Our executive officer was quite a character, an old steamboat man, rough in his manner but fair in dealings. He was never tired of telling how he, as captain of a gun’s crew at the battle of Shiloh, or Pittsburg Landing, had fired his guns from a gunboat with such effect that he was promoted. He kept the crew busy “holystoning” the gun deck to keep it clean, and was a capable officer.

U.S.S. Silver Cloud , Western River Squadron Tin Clad

Chapter V.

Naval Life.

The “Silver Cloud” had some antiquated weapons “boarding pikes” among them, large two-edged knife blades fastened in the ends of long poles, designed to be used at close quarters in case of a fight with enemies who might undertake to capture the boat by boarding her. These were used in drills, and for drills only, in the early part of my service, as remodeled Springfield rifles and cutlasses were the weapons used later. We had “single stick” exercises, the manual of arms, with an occasional shore infantry drill of the entire crew.

Our crew was a strange combination. The boatswain’s mate was a big, clear-eyed and intelligent fellow named Preston. We had some American, some Irish, some Swedes and some colored men. The last were an inexhaustible source of amusement to the officers, always lazy and hard to manage. The punishments for breach of rules, or disobedience of orders, were varied and severe. One big, good natured nigger, Solomon Andrews, had his name on the “log” kept by the officers of the deck, as being punished so frequently that each officer of the deck for a while made it a practice to inquire of the officer he relieved, “what is doing with Solomon?”

The “watches” commencing at 4 A. M., consisted of three four-hour watches ; two “dog” watches, from 4 to 6 P. M., and 6 to 8 P. M.; then two four-hour watches. So, as watch officer, I went on at four in the morning for four hours and, after two reliefs, came on again at four in the afternoon for two hours ; that was my “short day.” Next day I came on at midnight for four hours and after two reliefs of four hours each, came on again at noon for four hours and again at eight

27

o’clock for four hours. This was a “long day.” The third day, I came on at 8 A. M. for four hours and again at 6 P. M. for a two-hour watch. This routine gave me an average of about nine hours daily watch duty, but in daytime, “quarters,” boat drills, etc., were frequent. The watch officers on our boat were two of the ensigns (the executive officer did not stand watch) and two master’s mates.

It was the duty of the officer of the deck to be in uniform, wearing his sword, to communicate to the other officers, or the crew, all orders given by the captain or executive officer, which were written on a slate (or had been by the watch officer receiving them, and by him, turned over to the succeeding deck officer), to keep the “log,” a book which stated where we were, what boats passed up or down the river and any events of interest, noting drills, “quarters,” and other things showing the details of our daily occupation.

Our captain was an “acting master,” afterwards promoted to “acting volunteer lieutenant,” on account of bravery and good conduct in an action in which the boat he was on was engaged in Arkansas.

While slowly ascending the crooked waters of the Tennessee river, one morning, the quartermaster on “lookout,” who was stationed on the hurricane deck, over my head, I being officer on deck at that time, came down and reported “guerrillas ahead, on the shore.” He handed me the glass, and indicating the spot where he saw them, I looked through the glass and saw ahead a number of men who were evidently trying to conceal themselves behind logs, tree branches and brush. As several boats had been fired upon in this vicinity, we were keeping a sharp lookout. I at once reported to the captain and was ordered to give them a shell with the tenpounder rifled gun, which was loaded with a percussion shell. This was my first opportunity to use powder on the enemy, so I had the gun’s crew up at once and fired the gun, the

28

shell hit a tree and exploded, which caused the “Johnnies” to get out of their hiding place in quick time and retreat back into the woods. We followed up this shell with another one ; but, although we ran close to the shore, when we got to the place from which we had driven them, we could see no more signs of life. This little affair illustrates what the “tinclad” gunboats were for. With few guns and light iron protection for boilers, machinery and crew, they were terrors to the bands of Rebels who with muskets or small field pieces, could kill and wound pilots and crews of unarmed steamboats engaged in carrying troops or supplies in the rivers or engaged in peaceful occupations. The Mississippi and its tributaries had been opened up to navigation, but it was necessary to keep them open. Heavy and slow ironclads could not navigate the shallow river channels in which steamers had to go, and the light craft “tin-clads,” with no heavier armament than twenty-four pound howitzers, were a terror to these sharp-shooters. The twenty-four pound howitzer usually fired a shrapnel shell containing about eighty one-ounce musket balls, and the shell was filled with powder and sulphur, which would cause the shell to explode in from one to five seconds, according as its fuse was cut, the range of the gun being about one mile. These exploding shells were a source of fear to the enemy and set on fire any inflammable object they struck.

Our food was very plain. We had a “caterer” for our mess who purchased supplies, as he could, and prorated the expense among the members of the mess, collecting from them monthly. On one occasion, when I was caterer, we got some very strong butter. Our surgeon, who was young and “green,” thought he would improve it by having it “treated” by the cook, with some chemical. The cook “treated” it so that it looked very nice, but it tasted (and was, in fact) soap, after the “treatment.” Everyone who came to the table when it was first served, was furnished with hot biscuit and

29

helped himself to the nice looking butter. A sudden visit to the side of the boat was the next thing that happened and the f i nal result was that the cook was told to throw overboard all of the butter, but a little was kept, and melted, and run into bottles, afterwards being placed on the mess table when we had visitors, with labels marked “Dr. D’s Elixir of Butter,” until the joke got well known through our division.

I do not know how many of the tin-clads were in the squadron, but they were divided into separate “divisions” of eight or ten boats, each of which had a commanding officer. Our division commander was Lieutenant Commander S. L. Phelps, a regular navy officer, who was very much of a gentleman and who frequently made our boat his flagship. While he was on board, I was often required to act as his clerk, or secretary, and, while so acting, spent much time in the captain’s cabin, copying reports and communications to the Navy Department.

Captain Phelps treated me with great politeness, often insisted on my drinking tea with him (which he made himself in a silver tea service which he carried around with him). He was of a much more elevated class of man, to my mind, than most of the volunteer officers that I met. I learned that after the war he became United States consul at Acupulco, Mexico.

Chapter VI.

On the Mississippi.

Our period of service on the Tennessee River was brief, and we soon returned to Cairo and, after taking on coal and supplies, proceeded from Cairo down the Mississippi, passing a short distance below Cairo the famous “Island Ten,” on the Missouri side of the river, and Columbus, on the Kentucky side of the river. It was at Columbus that the Confederates expected to completely blockade the river from Union gunboats and transports, by means of heavy earthworks which they erected there on the river banks, planting heavy guns therein and stretching large chain cables across the river.

How the Union gunboats passed Columbus, and how the Union troops passed on the Missouri side of Island No. 10, after trees had been cut down to make a “channel” in high water, is a matter of much interest in the story of the war, but, as this had all happened before the period that I am speaking of, I will only allude to it here.

It was the custom of the “Silver Cloud” to keep in motion most of the daylight hours and to anchor at night at a respectable distance from hiding places for our friends the enemy.

I was daily becoming a little bit better posted in the drills and routine of the service. I was put in charge of the “forward battery” of two howitzers of twenty-four pounds calibre, each having a gun’s crew of nine men, whom I put through the drill which was given almost daily. There was also musket drill on the gun deck, “repelling boarders” in various parts of the boat, in which the boarding pikes were used, as well as single stick and cutlass exercises.

While officer of the deck on watch duty, I carried a

31

sword and revolver. The watch duty became rather tedious and monotonous, as there was so much of it.

There was always one of the crew on duty as lookout, generally a petty officer, called while on this duty, “quartermaster,” who was stationed on the hurricane roof immediately over my head. His business was to keep a lookout for boats or canoes crossing the river, for which purpose he was furnished with a small telescope, or spy glass, and he reported to the officer of the deck all approaching and passing boats, which the officer of the deck entered in the log book.

Most of the boats bound down stream we would hail for newspapers, which they always promptly furnished us, tying them to a board or stick and throwing the package into the river, from which we secured it by sending out a small boat. The two small boats which we used for moving around in, were known respectively as the “gig” and the “cutter.” The gig was always used by the captain, and the cutter by the officers and crew. It was the duty of the quartermaster to hail all approaching small boats by shouting “boat ahoy,” and the reply would indicate who was in the boat. If it was the captain the reply was “Silver Cloud,” if it was an officer, the reply was “Aye, aye, sir !” and, if some of the crew, “No, no, sir !”

Our captain or the captains of other gunboats visiting us, ‘were always met at the side of the boat as they stepped aboard, by the officer of the deck, who properly saluted them in the daytime, and, if at night, with lanterns in the hands of the members of the crew who were on watch at the time.

The service commenced to grow monotonous and irksome to me, meeting the same men and seeing the same faces day after day, and, when off duty, playing the same games of checkers, chess and backgammon (cards were not allowed), It was therefore a great relief for us to land at a city and have a few hours “shore leave.” At Memphis we usually

32

found one or two other gunboats and we tied up in their immediate vicinity, which gave us some opportunity to exchange civilities with the officers of the other boats.

On one occasion, while patrolling the river, we came across the wreck of a large steamer, which had been loaded with army stores, and was en route south, when sunk. The cargo consisted mainly of hams and sugar, and, as it had been abandoned, we went alongside of the wreck and took off as many of the wet hams as we could and hung them up on lines stretched across the hurricane roof, to dry out as well as possible. We also took several barrels of wet sugar. What to do with the latter was a conundrum to us until somebody suggested that we land at a plantation on the Arkansas side where great quantities of watermelons were to be had, which we did. We secured all the watermelons we could by purchase from the darkies and then proceeded to make a barrel or two of “watermelon rind preserves” by using the rinds of the watermelons after they had been cut up into small blocks, peeling them and then boiling them with the sugar, thus providing ourselves with very palatable preserves.

On returning, when nearing Memphis, somebody suggested we had better take down our hams, as there was an officer by name of Patterson who was called “commandant,” who would see these hams and ask all sorts of questions about them. We took the hams down and used them up later, as best we could, which was a wise thing for us to do, as another gunboat came into Memphis shortly afterwards with a string of wet hams hanging up to dry, which Commandant Patterson required the gunboat officers to inventory and account for, at some price, to the War Department, as technically the hams were the property of the War Department, but as a matter of fact their value scarcely equaled the labor and trouble of getting them out and drying them.

My messmates were interesting as acquaintance de

33

veloped their characteristics. Frank M., one of my fellow master’s mates, was a quiet, unassuming sort of a fellow, from Syracuse, N. Y. He was fond of answering the advertisements of young ladies for “correspondence with naval officers,” which frequently appeared in the Waverly Magazine and other weekly literary papers of the day ; but he was not very energetic, and one of his lady correspondents wrote to him so often that he got tired of her letters and asked me to take her letters off his hands. This young lady assumed to be a student at a female college in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Her letters were very sprightly, and telling her that at Frank’s request, I would offer myself as a substitute correspondent, I was accepted as such and occupied many leisure hours afterwards writing answers to her letters, which I always signed “Frank M.” and never disclosed my identity. My surprise can therefore be imagined, when a newspaper notice of my marriage more than a year after the war was ended and I had returned to civil life, the correspondence having ceased nearly two years was cut out of a newspaper in which it had appeared, pinned to a sheet of note paper, and under it written, “Perfidious One,” with the signature, “Your Yellow Springs Correspondent.” This was sent to me at St. Louis, showing that the young lady not only had in some way found what my name was, but also had ascertained my address.

The first clay of January, 1864, was the coldest day that I ever knew in the southern country. At Memphis, where the “Silver Cloud” was then lying, the river was full of floating ice of great thickness and the pieces of ice were so heavy, hard and sharp that the steamboats were laid up, waiting for the ice to become soft and of less quantity in the stream, as it was feared the grinding of the ice would cut through the planking of the hulls and sink the boats. It was very unusual for ice to be so thick and so hard and in such quantities as far south as Memphis.

34

At this particular time General Sherman and his staff came to Memphis. He was very anxious to proceed immediately down the Mississippi river to Vicksburg, so one of his staff officers visited the various gunboats at Memphis and made inquiries as to the possibility of carrying the general and his staff down the river, without delay.

Our captain and senior officers decided that it was worth while for us to try it, to accommodate General Sherman, so we at short notice got on board a lot of two-inch pine plank, sawed up into two-foot lengths, a lot of long spikes, some hammers, stages and lanterns. The object of these preparations being that, in case the ice should grind our hull seriously, we would by means of the stages dropped over the gunwales, spike on some of these pieces of plank so that they would stand the grind, rather than the hull.

Without waiting to get on board fresh provisions, which we needed to supply our distinguished company, we got on our way and, of course, went very slowly, but successfully got down to Vicksburg, where we remained for two (lays, giving us all an opportunity to see the wonderful place which had been surrendered by General Pemberton, C. S. A., to the Union army under General Grant on the 4th day of July, six months before this time. We then started back up the river, but still without any better provisions than we left Memphis with, as Vicksburg was a simple military post and its garrison and inhabitants had been obliged to subsist considerably on mule meat during the latter part of the siege.

While I was on deck, after leaving Vicksburg, our boat, having proceeded about twenty miles up the river, I saw a small sand island, called in the pilot’s vernacular, a “towhead,” literally covered with geese, ducks and sandhill cranes, the large number being no doubt congregated there by reason of the excessive cold weather. It occurred to me that here was a chance to lay in some fresh provisions, and, asking the cap

35

tain’s permission to fire one of my twenty-four pound bow howitzers at this flock of birds, I brought the boat slowly up to the island, as near as I could, without frightening the birds away. I then stopped the boat and fired my gun and, by some extraordinary piece of good luck, happened to explode the shell just on the edge of the island. The birds of course rose with the sound of the explosion. As near as I could estimate the distance, I had fired the gun at a range of a mile. Our boat being brought to anchor, I went to the island in the cutter and found a large number of dead birds and some fluttering and badly wounded, which the boat’s crew and myself finished, either by striking them with the oars, or shooting them with revolvers. On returning, the number of dead birds we brought, turned out to be forty-three, of which the large majority were geese and ducks. I had the satisfaction of being patted on the shoulder by our distinguished passenger, General Sherman, and told by him that “we could now have some change of diet,” owing to my good shot. This proved to be the case. We gave the sandhill cranes to the crew, they having a rank flavor and requiring to be boiled, or parboiled, to get this flavor out somewhat, so that they could be afterwards roasted and eaten.

I have often told this story at dinners of naval veterans, etc., but always prefaced it with the statement that “I once killed forty-three geese and ducks with one shot,” which, from the above statement, will be seen was a fact.

Some years ago, I was called on by a little old man at my office in Chicago, who inquired for me with a peculiar high pitched and squeaky voice. I at once recognized him as a man who had been one of the crew of the “Silver Cloud.” He said he wanted my signature to some pension papers he was sending to Washington. I at first pretended not to be able to recognize him, when he pulled from his vest pocket a small black object, which he told me was the skin of one of the sandhill cranes’ feet that I shot just above Vicksburg and

36

that he had brought that with him to prove to me that he was the man that he claimed to be. I signed his paper with alacrity, on the production of this proof of his identity. At a dinner of a naval veteran society in Chicago, subsequently, at the Union League Club, where there were several guests invited by the members of the society, I was called on to tell my “duck story,” which, like many sailor’s yarns, was considered by those who had heard it before, as a little bit exaggerated. I was so pressed to tell the story that I did so and, when several sarcastic remarks to the effect of “couldn’t I reduce the number of ducks one or two,” were made, to my utter astonishment, one of the guests, a tall, gray-bearded old man,arose in his place and said that “he saw that shot and counted the birds and there were forty-three.” I immediately said to this gentleman that I was unable to locate him and asked him for some details of his welcome corroboration of my story. He said that he was General Bingham, at this particular time stationed at the headquarters in Chicago of the Department of the Lakes of the United States army as chief quartermaster. He said that in 1864 he was captain and quartermaster on General Sherman’s staff, and was one of the party that we took on our boat from Memphis to Vicksburg, and he had always remembered the great success of that howitzer shell, particularly as it produced a lot of fresh provisions in the shape of geese and ducks, instead of the “salt horse” of which they had had so much and were so tired.

This statement from so distinguished a man on such an occasion was very gratifying to me and led to quite a friendship between General Bingham and myself.

Chapter VII.

Fort Pillow.

In April, 1864, occurred the Fort Pillow massacre. The part that the “Silver Cloud” and myself took in that, can perhaps be best told by giving a copy of a letter which I wrote to Congressman Blow and which he had published in the New York Times of May 3rd, 1864, which is subjoined :

UNITED STATES STEAMER “SILVER CLOUD.”

Mississippi River, April 22nd, 1864.

SIR:-Since you did me the favor of recommending my appointment last year, I have been on duty aboard this boat. I now write you with reference to the Fort Pillow massacre, because some of our crew are colored and I feel personally interested in the retaliation which our government may deal out to the rebels, when the fact of the merciless butchery is fully established.

Our boat arrived at the fort about 730 A. M. on Wednesday, the 13th, the day after the rebels captured the fort. After shelling them, whenever we could see them, for two hours, a flag of truce from the rebel General Chalmers, was received by us, and Captain Ferguson of this boat, made an arrangement with General Chalmers for the paroling of our wounded and the burial of our dead ; the arrangement to last until 5 P. M. We then landed at the fort, and I was sent out with a burial party to bury our dead.

I found many of the dead lying close along by the water’s edge, where they had evidently sought safety ; they could not offer any resistance from the places where they were, in holes and cavities along the banks ; most of them had two wounds. I saw several colored soldiers of the Sixth United States

38

Artillery, with their eyes punched out with bayonets ; many of them were shot twice and bayonetted also. All those along the bank of the river were colored. The number of the colored near the river was about seventy. Going up into the fort, I saw there bodies partially consumed by fire. Whether burned before or after death I cannot say, anyway, there were several companies of rebels in the fort while these bodies were burning, and they could have pulled them out of the fire had they chosen to do so. One of the wounded negroes told me that “he hadn’t done a thing,” and when the rebels drove our men out of the fort, they (our men) threw away their guns and cried out that they surrendered, but they kept on shooting them down until they had shot all but a few. This is what they all say.

I had some conversation with rebel officers and they claim that our men would not surrender and in some few cases they “could not control their men,” who seemed determined to shoot down every negro soldier, whether he surrendered or not. This is a flimsy excuse, for after our colored troops had been driven from the fort, and they were surrounded by the rebels on all sides, it is apparent that they would do what all say they did, throw down their arms and beg for mercy.

I buried very few white men, the whole number buried by my party and the party from the gunboat “New Era” was about one hundred.

I can make affidavit to the above if necessary. Hoping that the above may be of some service and that a desire to be of service will be considered sufficient excuse for writing to you, I remain very respectfully your obedient servant,

ROBERT S. CRITCHELL,

Acting Master’s Mate, U. S. N.

In the spring of 1865, a Confederate ironclad gunboat, which was also a ram, which they had constructed in Red

39

River, ran through a number of our gunboats which were anchored at the mouth of the Red river to prevent her egress into the Mississippi, doing so at an early hour in the morning when it was rather foggy, and, having passed the gunboats successfully, went on down the Mississippi. This seemed to create quite a commotion in the Navy Department, and as soon as the news could reach Washington, nearly all the gunboats on the Mississippi, below Memphis, were ordered to proceed at once to the mouth of Red river, it apparently being feared that there was another ironclad up the Red river constructed by the Confederates, which it was desired to head off at all hazards. The “Silver Cloud,” was among those ordered to the mouth of the Red river. The water in the Mississippi was very high at the time, and, as our pilots did not know the channel of navigation, we were ordered to follow a gunboat called the “Mist,” keeping four hundred yards astern of it. Just before daybreak one morning, while we were following the “Mist,” it became foggy and without warning or signals to us, the “Mist” “rounded to” for the purpose of landing. I was on deck at the time and the first knowledge I had, or our pilot either, that the “Mist” was going to land, was when we found ourselves in collision with her. We struck her about “midships,” cutting her guard in two and cutting a hole in her hull, through which the water commenced to pour into her very rapidly. The officers and crew of the “Mist” were naturally panic stricken at the sudden and unexpected crushing in of the side of their vessel. They immediately commenced to climb on our boat, thinking theirs was doomed to sink. Our executive officer got a number of our crew aboard of her, pulled her guns with every possible haste over to the side opposite the one crushed in, and in that way got most of the hole in her hull above the water line. We then nailed canvas hammocks over the hole and stopped the water from coming in.

40

By this time the people on the “Mist” had recovered from their panic and commenced to pay some attention to the men who were hurt by being crushed and jammed as they lay on the deck, or in their hammocks, opposite the place where we struck her. The “Mist” was soon safely repaired and proceeded on her way to the rendezvous, where it became my duty as officer of the deck on duty at the time, to write a description of the accident for the Navy Department, which when done, read something like a comic opera, as I had to describe how the “Silver Cloud” following the “Mist” in a fog, collided with the “Mist” and did considerable damage, the accident being due wholly to the failure of the officers of the “Mist” to signal the “Silver Cloud” that they were about to stop and land on account of the fog.

Chapter VIII.

FATE OF A “GALLANT” OFFICER.

When I was first ordered aboard the “Silver Cloud” she was commanded by Acting Volunteer Lieutenant 0-. Captain O- was very popular with the officers and crew, was very much of a “dandy” and was a great “ladies’ man.”

On one occasion when we were at Memphis, Tenn., the wife of an officer of higher rank than he, was very anxious to get to her husband’s vessel, which at the time was several hundred miles below Memphis. In the captain’s cabin there were several unoccupied staterooms, and there was no difficulty in the way of the lady’s getting from Memphis to her husband’s boat except that of propriety. She was young and pretty, and there were no ladies on our boat. As we had to go very slowly in order to keep a close lookout for guerrillas along the banks, who constantly were firing upon unarmed transports, she would have to be on board two days and two nights. She finally came on board, and much talk was created at the officers’ mess tables.

When the “Silver Cloud” came alongside of the boat commanded by the lady’s husband, the face of the aforesaid husband was a picture to look at. He evidently did not think she had done the right thing and he was so positive about this that, in the opinion of everybody who knew anything about it, it was his influence with the Navy Department at Washington that procured the transfer of Captain 0— from the “Silver Cloud” to one of the smallest armed vessels in the Mississippi squadron, then stationed on the Cumberland river. Life was not wholly tedious on the “Silver Cloud” on

42

the lower Mississippi. The monotony was broken by the passing of steamers, occasional firing at guerrillas on the banks, the frequent landings at Memphis, Helena and other places where there was considerable population, and large bodies of troops ; but up where Captain 0- was sent there was no life whatever and the service was desperately dreary.

This happened in 1863 and my resignation was accepted in 1865. I often wondered what became of Captain 0-, and my curiosity in regard to his subsequent career was gratified in a very singular manner. Along about 1868 or 1869 I was traveling on a railroad train in Illinois, and I found in the seat a Methodist weekly paper, which had been left by the previous occupant. As I had several hours on the train I read the paper to pass away the time. Among other things that I noticed in it was an article on the “Power of Prayer,” which went on to state that a certain Captain 0—, formerly of the United States Navy, and more recently connected with the Erie railroad, in New York City, was accused of breaking up the home of a citizen of New York. During the pendency of divorce proceedings 0—- appeared to give testimony in behalf of the wife in a court room, and the injured husband, being present, as soon as began to testify, drew a revolver and shot O—- dead. The husband was put on trial formurder in the first degree, for which the punishment was death. When the case was given to the jury, that body stood eleven to one for conviction on this charge. The one man, it appears, was a Methodist, who, after using every possible argument with his fellow jurymen unsuccessfully, dropped on his knees in the jury room and uttered a very eloquent prayer. In it he pictured the mental condition of the injured husband, expressed the hope that no one of his fellow jurymen would ever have put before them such a temptation to kill as this husband had, but, if one should be so tempted, he prayed the Almighty

43

that the jurymen would find mercy in their hearts and would vindicate the law by a penitentiary sentence and not by death. His plea, in this manner, was effectual ; and the jury, after he arose from his knees, found the lightest possible penalty, which was for a short term of imprisonment. And this was the end of my former commanding officer.

Chapter IX.

RE-ENTERS INSURANCE.

In 1865 the news we were able to get indicated that the war was rapidly drawing to an end, and within a few months the “Silver Cloud” was ordered to Cairo. Here we received with much satisfaction the information that each officer would be permitted to send in his resignation, which would be promptly accepted, or, if he preferred it, he could apply for a sixty-day leave of absence and then tender his resignation as of the date the leave of absence expired. I chose the latter plan and with much joy left the boat at Mound City, Ill., seven miles above Cairo, on the Ohio river, which place was designated as the “boneyard,” as it was where the gunboats were dismantled and the crews paid off and discharged. I took the train at Mound City for St. Louis, and on arriving there was at once offered the position of special agent for the Home, of New York, which I gladly accepted.

You must log in to post a comment.